|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forthcoming meetings

| Speaker Meeting | |

| Annual General Meeting | |

| Date: | Friday, June 06, 2014 |

| Time: | 19:30 |

| Subject: | Astronomy for Mapmakers |

| Speaker: | Roy Wood |

| Location: | The Mencap Centre, Enborne Road, Newbury |

| Beginners Meeting | |

| No beginners meetings currently scheduled in the diary. | |

| Observing Session | |

| No observing sessions currently scheduled in the diary. | |

| Special Meeting | |

| No special meetings currently scheduled in the diary. | |

|

|

|

|

|

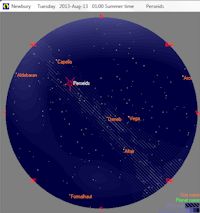

Perseid Watch 2013 The Perseids are favourable this year with no interference from the moon, and we can take advantage of the longer hours of darkness as summer draws to a close. The peak of activity is on the afternoon of Monday 12th August so rates should be highest that evening, but the peak is broad so there will still be respectable numbers on nights either side of maximum. The radiant is higher later in the night so it's worth staying up, and the longer you watch the better your chances of catching the occasional bright meteor which the Perseids are well known for.

The sky chart shows the position of the radiant at local midnight but meteors can be seen anywhere in the sky. The grey areas on the graph show when the moon is above the horizon and the yellow bars show the evenings when the greatest Perseid activity is expected. The lighter blue lines show the extent of the shower a few days either side of maximum. Sunset is about 9pm and sunrise about 5am.

Archive from previous Perseid Meteor Showers Fireball report from Witney in Oxfordshire I'm in Hardwick, just south of Witney in Oxfordshire and around 11 pm-ish (Saturday 7th August), there was the most spectacular fireball reminiscent of the Leonids back in the late 90s. I'm afraid am a bit rusty on my constellations at present and cannot be more precise as to where last night's radiated from but it headed south-west, I hope one of your members spotted too.... and some quite persistent significant other meteors. I hope this augurs a wonderful display this week (clouds permitting!)... will be out again tonight but as soon as it gets dark! I will try and work out how to keep my camera shutter open for 30 seconds and see if I can capture a one in a million shot!! Further note: David Boyd of Newbury AS saw the bright flash created by this fireball, but was not quite looking in the right direction when it burned its way across the sky. Have you captured a Perseid on camera or film?

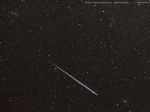

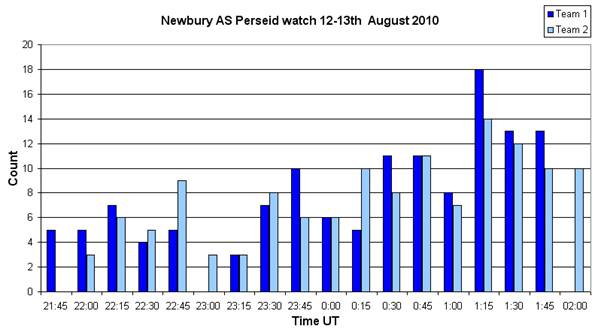

Disclaimer We wish to make it clear that Newbury Astronomical Society is not responsible for content posted on either the @NewburyAS Twitter feed or newburyas.wordpress.com. In April 2010, the @NewburyAS twitter feed was taken by Adrian West for his own personal use and renamed, the replacement @NewburyAS feed is also under his control. Should you wish to check the validity of any accounts that appear to be connected with us please email [email protected] or tweet @NewburyAstro Click an image to enlarge or see a slideshow. Full description is on the enlargement. Newbury AS observations of the Perseid meteor shower on 12/13 August 2010 On the night of 12/13 August 2010, the predicted peak of the Perseid meteor shower, several members of the society gathered at Wilcot Village Hall in Wiltshire to observe the meteors under wonderfully dark skies. For the first time in many years we were fortunate to have both clear skies for most of the night and no moonlight so conditions were near perfect to enjoy the display. Five members of the society, David Boyd, Ann Davies, Bob Ferryman, Steve Harris and Kath Nurse (Team 1) counted and recorded meteors from 21:45 to 2:00 UT. Richard and Nicky Fleet (Team 2) observed alternately for an hour each from 22:00 to 2:15 UT. The bar chart of our results shows the meteor rate rising to a peak around 1.30 and then falling. There is good consistency between the counts of both teams. We are contributing these results to the Perseid observing campaign being coordinated by the BAA.

Richard Fleet also operated a pair of DSLR cameras and recorded several meteors including one very bright fireball which dazzled us all. You can see his photos by clicking here. Mark Harman, John Napper and Colin Stevens from Newbury AS plus several members of Reading AS and some Wilcot residents joined us to enjoy the show. Besides observing meteors, Nicky also sustained us all with hot soup and kept the world informed of our activities on twitter. It was a night to remember, probably the best meteor display many of us had ever seen.

How many meteors will I see?

We talk about meteor ‘showers’, but the word shower is something of a misnomer as far as meteors are concerned. Throughout recorded history there have only been a handful of examples of the kind of display that many people would imagine as a shower. Even at the peak of the Perseid meteors, if you expect to see at least one meteor a minute you will often be disappointed. Expecting to see a meteor every few minutes is far more realistic but, just like London buses, it's not unusual to wait ages and then find several come along at once! If you go out expecting to see 5 meteors an hour and manage to see 10 you'll be delighted; expect to see 100 but only see 10 and it’s a flop. When people talk about meteor numbers what they are usually quoting is the Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR). This is an idealised figure which assumes excellent sky conditions with the radiant (the area from which meteors appear to come from) directly overhead. This allows useful comparisons of meteor activity from hour to hour, day to day and across the years. Using the maximum ZHR we can see that some showers, such as the Geminids in December, have strengthened significantly over the last century; while others, such as the Leonids in November, show large variations in activity from year to year. The rate quoted in the headlines is usually the maximum for a shower but unfortunately the rate can vary by the hour so very often there isn't even a single number which applies to the whole night! Where do these figures come from? The visual rates are mostly calculated from data gathered by small bands of dedicated amateur observers who spend many hours meticulously recording the meteors they see, along with enough information to arrive at (amongst other things) the ZHR. These are the real heroes of #Meteorwatch because without their work we wouldn't know what to expect, and even the best models still need observations to check the results. If you would like to help with this work visit the BAA meteor section pages and the International Meteor Organization (IMO) website. So how does all this translate into what the average suburban dweller might see at maximum? Lets start with someone at a reasonably dark site. Typically they would see around 5 random, or sporadic, meteors per hour on any moonless night of the year. If we then get a shower with a predicted ZHR of (say) 100, you might think they would get to see around 20 times more meteors than on an average night. However, this assumes the radiant is overhead. Unfortunately the lower the radiant is the fewer meteors will pass through the visible area of sky. For the Perseids, at midnight in the UK, the radiant is only 45 degrees up so this reduces the likely rate to about 70 meteors per hour - even under the darkest skies. Now allow for the light pollution that we all live under which affects the limiting magnitude, that is the faintest stars we can see. There are generally many more faint meteors than bright ones, so orange-lit skies can rapidly reduce the numbers visible. Even in a semi-rural area where you can clearly see the Milky Way this can knock enough off the limiting magnitude, to reduce the rate to 30 per hour. Move to a small town such as Newbury and you could lose almost another magnitude, so the rate would drop to around 15 per hour. By the time you get to the London suburbs only the brightest meteors are visible and the rate could be as low as 5 per hour - but the ZHR figure is still 100 per hour! This is not intended to put anyone off but rather to emphasise that, if you go to a secure, dark location, you can dramatically improve the number of meteors you will see. The brightest meteors are the ones people enjoy most, and many of these will still show through light polluted skies - so all is not lost even in the suburbs. Also don't forget that predictions are just that, we don't have a detailed enough knowledge of where all the debris that causes meteors is, so there is always room for pleasant surprises if we hit a denser patch. So – if you want to see more meteors – go to the darkest spot you can find (away from street lights), on the nights around the predicted maximum, look up and see what there is to see! A useful guide to sky brightness in your area is the night sky simulator on the Needless website.

Meteors aren't the only streaks in the sky In theory, imaging meteors could hardly be simpler, just point the camera at the sky and leave the shutter open for long enough. In practice you will have to take a lot of images to get more than a handful of meteors. Meteors are so brief and move so fast that there isn't time to expose much of the film or digital sensor, so it is usually only the brightest fireballs that produce impressive images. What appears to the eye as an obvious meteor barely shows up on an image, a good example of just how powerful the human eye can be. One of the problems with imaging meteors today is that the sky is now so full of man-made objects that you are far more likely to record them than a meteor. To the eye a meteor is obvious because of its fast movement and short duration. On a photograph this shows up a streak of light, but so do satellites and it can be easy to mistake a satellite trail for a meteor, particularly if you weren't watching at the time. Things like planes are easy to pick out, the red and green or flashing lights are a bit of a giveaway. Mostly satellites show as a steady track, across several frames if a series is taken, and are fairly easily recognised. Sometimes though it isn't quite so obvious so it pays to check, here are a few examples of what to look out for:

Link to Previous Meteorwatch Pages

|

||||||||||||